Why Winter Training Actually Matters

Most cyclists treat winter as something to survive. Get through December to February without losing too much fitness, then rebuild in spring. I used to think the same way, grinding through endless base miles in the Kent rain. That's backwards.

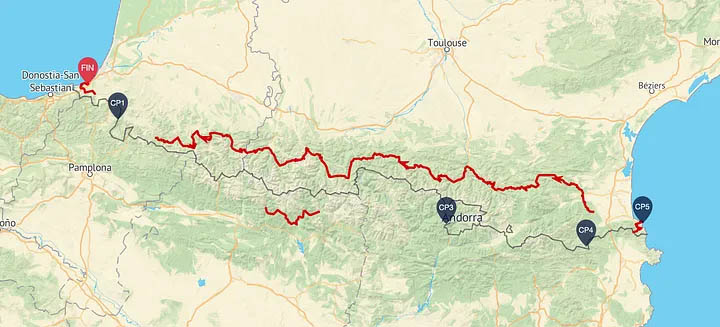

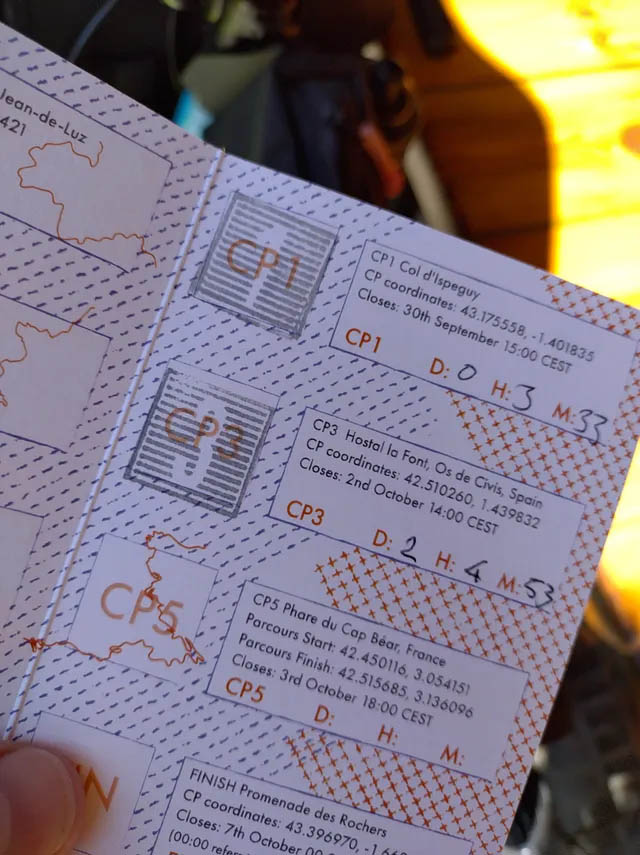

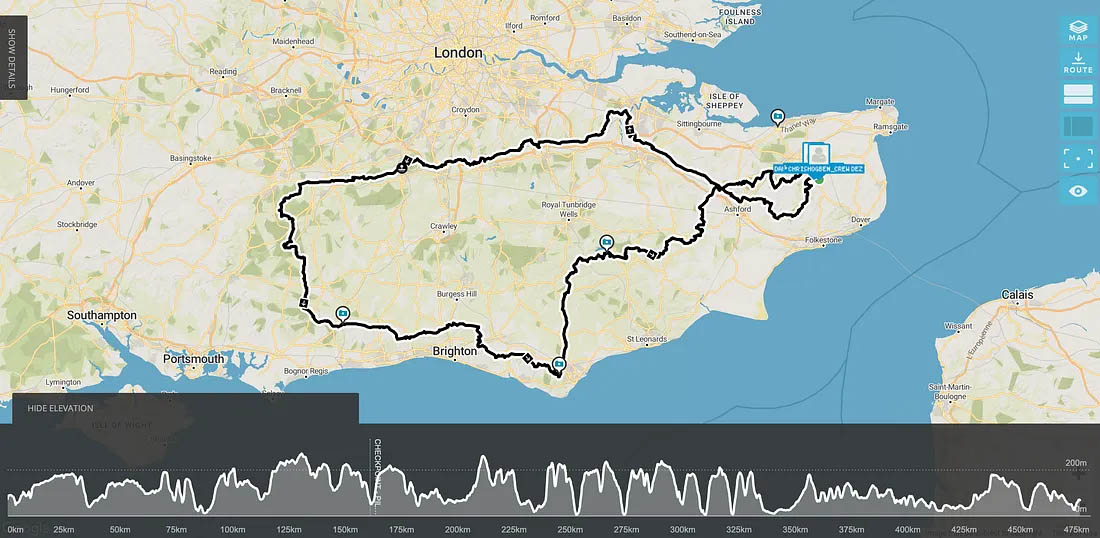

This is especially true if you're training for ultra-distance events. Riders planning a 300km audax in July or a multi-day tour in August often panic about winter volume. They think they need those long base miles now or they'll never be ready. The research suggests otherwise.

Winter isn't a holding pattern. It's an opportunity to train in ways that simply don't work in summer. The cold acts as a physiological stimulus. Shorter days force you into time-efficient training blocks. And while other riders are doing slow miles in poor conditions, you can be doing the work that actually maintains your top-end fitness.

The research backs this up. More importantly, it works in practice for riders targeting everything from century rides, L'Etape du Tour or Paris-Brest-Paris. Here's what you need to know.

Keep Your Muscles Warm (This Isn't About Comfort)

What to wear

Below 15°C, you need thermal bibs. Not summer bibs with leg warmers. Proper thermal bibs with a fleece lining. Below 10°C, add knee warmers over the top. Yes, over thermal bibs. The knee joint haemorrhages heat. Below 5°C, you want overshoes as well. Numb toes aren't just uncomfortable, they're a sign you've lost power output.

One more thing. Overdress your legs, underdress your torso. Your core generates heat. Your legs don't, not enough anyway. This took me a while to learn properly. In British winter, where the damp cold finds every gap in your kit, getting the layering right makes the difference between a quality session and just suffering.

Why this matters

Stephen Cheung's lab at Brock University found something remarkable. When your skin gets cold, even if your core temperature stays normal, your time to exhaustion drops by 31%. Not a few per cent. Thirty-one. The mechanism is straightforward. Cold skin slows nerve conduction velocity. Your brain limits how many muscle fibres it recruits because it's trying to conserve heat. You're not weak. You're mechanically limited.

Keep your muscles at operating temperature and you keep your power output. It's that simple.

Common mistakes

The biggest one? Comparing your winter watts to summer numbers. Riders panic when they see lower power numbers in January and assume they're losing fitness. Stop it. You're fighting increased air density in cold weather, which creates more aerodynamic drag. Add road resistance and usually a headwind, and your normalised power tells you nothing about fitness in January.

A better measure? Look at your power-to-heart-rate ratio. If that's stable across the season, your fitness is fine. The lower absolute numbers are environmental, not physiological.

Second mistake: thinking you'll warm up once you're going. You won't. Not properly. If you leave the house underdressed, you'll be underdressed for the entire ride. Third: numb extremities. If you can't feel your toes or fingers, you've already gone too far. Turn around.

Train in Blocks, Not Lines

The protocol

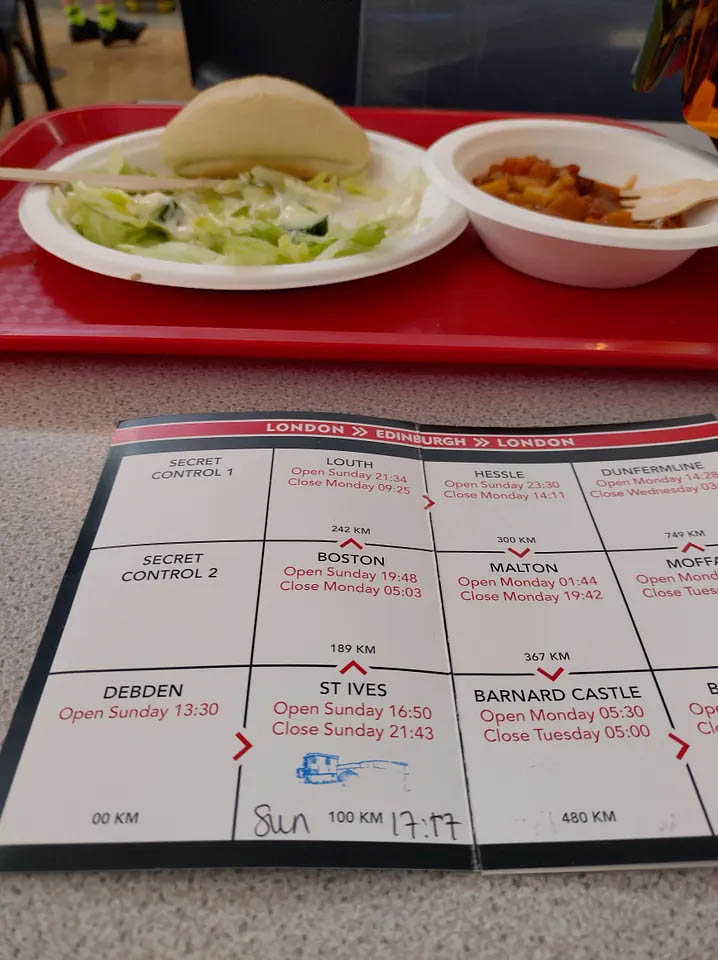

Here's what actually works when you've only got six to eight hours a week. Week one: four or five hard sessions. Intervals, tempo, threshold work. Doesn't matter hugely which, as long as it's quality. Weeks two and three: one hard session per week. The rest is easy or recovery. Properly easy, not "I'm just going to push this climb" easy. Then repeat the three-week cycle.

That's it. No complicated periodisation charts. No spreadsheets. Just three weeks of very different training stress.

Why this works

Bent Rønnestad's research group in Norway tested this exact protocol against traditional training. Same total volume. Same total intensity. Just organised differently. The block periodisation group improved VO₂max by 4.6%. Power output at lactate threshold went up 10%. The traditional group, spreading their intensity evenly across the month, saw no significant changes at all.

The theory is something called cumulative fatigue and delayed adaptation. You hammer yourself for one week, which creates a significant training stress. Then you back right off, which allows the adaptation to express itself. The traditional approach never creates enough stress to force adaptation, but also never allows enough recovery to realise it.

Winter makes this practical. You can do your hard week when conditions are good. Then when the weather turns awful, you're in your recovery weeks anyway.

What this means for ultra-distance training

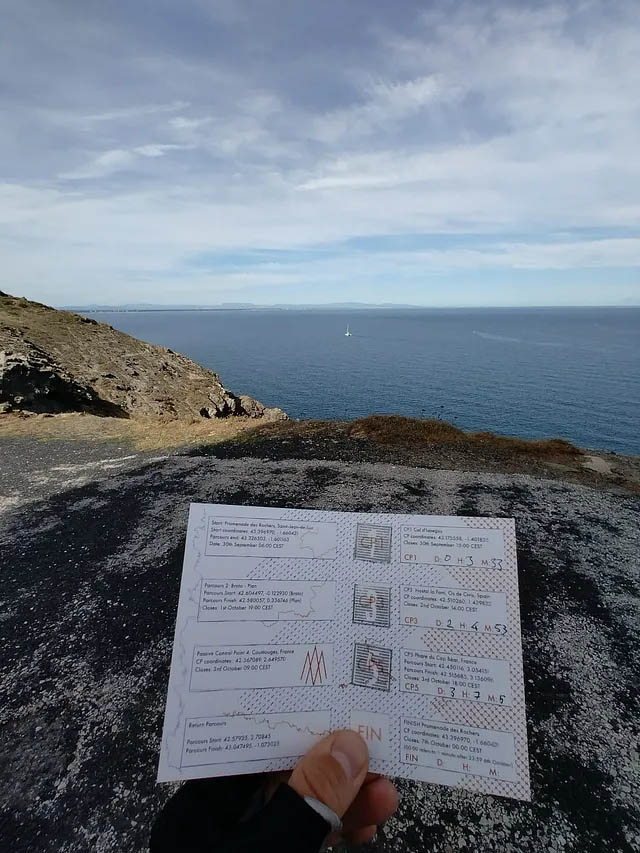

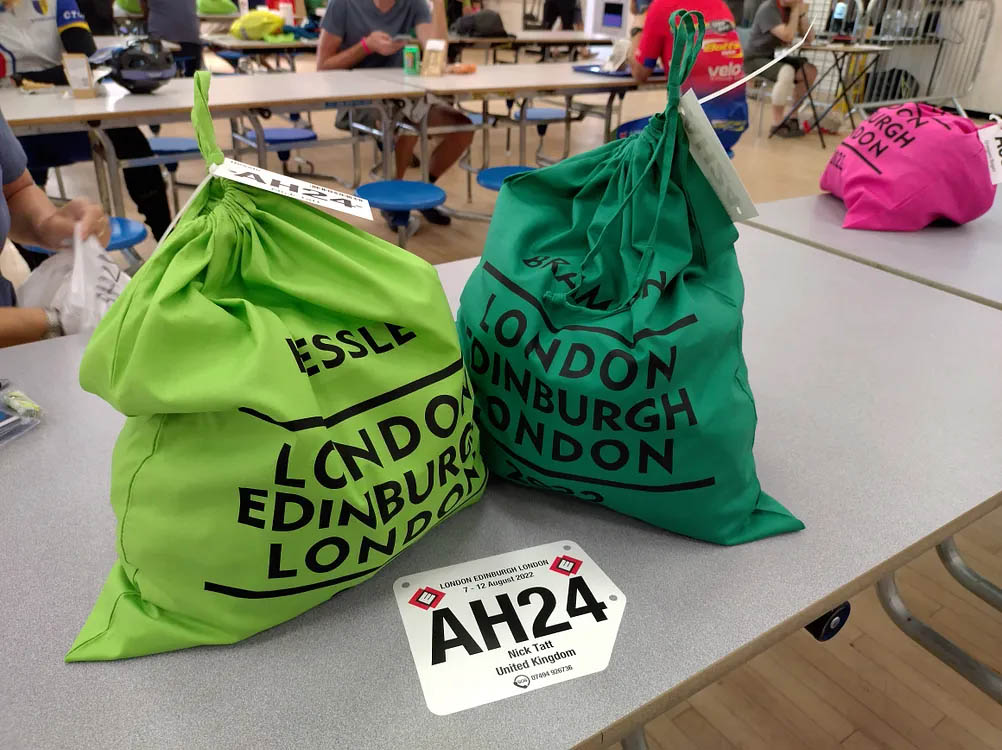

This is where riders planning long summer events often get it wrong. If you're targeting a 300km audax in July, a LEL in August, or any multi-day tour, you're probably panicking about winter volume right now. You think you need to be doing 15-20 hour weeks in December to build the base for summer.

You don't. What you need in winter is to maintain your ability to produce steady power. That's intensity work, not volume. If you're only riding six hours a week through winter using block periodisation, you'll produce superior adaptations compared to grinding out twice that volume in poor conditions. The fitness you're building now is the foundation for the volume you'll add in spring.

Quality beats quantity. Always has, but especially when conditions limit your training time. For ultra-distance events, winter is about maintaining your ceiling and your steady-state power. The long rides come later, when you've got daylight and better conditions. Riders doing 15 hours of slow winter miles are getting some fitness benefit, but far less return per hour invested. More importantly, they're often arriving at spring tired rather than ready to build.

The volume will come. But it comes more productively when you've maintained your ability to ride at a decent intensity. That's what block periodisation preserves through winter.

Never Train Through Shivering

The hard rule

When you start shivering, the session is over. Add a layer if you've got one. Otherwise, go home. Not in five minutes. Now. If you get indoors and you're still shivering after five minutes, you stayed out too long. Learn from that.

I used to ignore this. Thought pushing through made me tougher, especially on long training rides. Then I started looking at the power files from those sessions. The last hour was always rubbish. I wasn't being tough, I was wasting time and depleting glycogen.

Why shivering changes everything

Shivering can double your metabolic rate. Sounds good, right? More energy expenditure? No. Because shivering burns glycogen, fast. It's your body's emergency heating system, and it runs on your sprint fuel. Once you're shivering, you're not building fitness. You're depleting your carbohydrate stores and sabotaging tomorrow's session.

There's another consideration. When you're not shivering but you're in cool conditions, brown adipose tissue activates. This increases your resting metabolic rate slightly and shifts fuel oxidation towards fat. But that benefit disappears completely once shivering starts. The difference between beneficial cold exposure and destructive cold exposure is whether you're shivering. That's your line.

What shivering tells you

Usually, it means you underdressed. Sometimes it means you went too long. Occasionally it means you didn't eat enough during the ride. Whatever the cause, the solution is the same. Stop. There's no toughness points for finishing an interval set while shivering. You're just making yourself slower.

For ultra-distance riders, this is particularly important. The temptation is to push through on long winter rides because you think you need the time in the saddle. You don't. Not if you're shivering. That's junk miles, and they're counterproductive.

When to Train Outside (And When Not To)

The approach

Get outside once or twice a week when conditions allow. Dry roads, daylight, temperature above freezing. Keep these rides to 60 or 90 minutes. Make them quality, not epic. Use the turbo for your longer sessions, your harder sessions, or when the weather's genuinely dangerous.

I use indoor training for structured work. No shame in that. But I also make sure to get outside when conditions are reasonable. Partly for mental health, partly because riding outdoors maintains the skills and confidence you need for longer events. There's also a physiological reason.

The cellular signal

Research from Dustin Slivka's group shows that exercising in cold temperatures, around 7°C, increases expression of something called PGC-1α. This is the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. It's the genetic signal that tells your cells to build more aerobic machinery. You get this signal training indoors as well, just from the exercise itself. But the cold appears to amplify it. Think of outdoor cold training as an additional stimulus, not a replacement for structured indoor work.

The catch? This is an acute molecular response. To turn that signal into actual fitness requires consistency over weeks and months. It's not a shortcut. It's just another tool.

Be realistic about this

Don't ride in dangerous conditions chasing "cold benefits". Ice, severe cold, no visibility? Stay inside. The marginal gain from cold exposure isn't worth the injury risk or the rubbish training session. Indoor training works perfectly well. But if conditions are reasonable, getting outside adds something. Exactly how much is hard to quantify, but the research suggests it's not nothing.

In British winter, we rarely deal with extreme cold. More often it's damp, grey, and windy. Pick your days. When the roads are dry and you've got daylight, get out. When it's bucketing down and blowing a gale, that's what the turbo is for.

Get Warm Fast After Hard Efforts

The 30-minute window

As soon as you finish, get this done. Strip off immediately. Not after you've put the bike away. Not after you've checked Strava. Now. Hot shower or at least a warm room. Your core temperature needs to come back up. Eat 30 to 50 grams of carbohydrate plus 20 grams of protein. A recovery shake works. So does toast and peanut butter, or a bowl of porridge. Drink 500 to 750ml of fluid. Warm is better than cold, purely because you'll drink more of it.

Why the rush matters

Hard training temporarily suppresses immune function. Research by David Nieman and others has shown this "open window" effect clearly. Your body's first line of defence drops for several hours after intense exercise. Add cold stress on top and you've likely created a bigger immunological challenge. The faster you rewarm and get carbohydrate in, the faster cortisol drops back to baseline. That helps close the vulnerability window.

This isn't theoretical. You probably know this already if you've ever finished a hard winter ride, cooled down slowly, then been ill three days later. The connection is real. For riders training for summer events, getting ill in January or February doesn't just cost you a week. It costs you the cumulative training you'd have done across that week and the recovery period after.

The hydration trap

Here's something most cyclists don't realise. Cold air suppresses your thirst response. The hormone that makes you feel thirsty, arginine vasopressin, doesn't trigger properly in the cold. Meanwhile, you're losing fluid through respiration. Every breath out in cold air is visible moisture leaving your body. Plus cold-induced diuresis means you're losing more fluid through urination. Net result: significant dehydration without feeling thirsty.

Drink by the clock. 500ml per hour, whether you feel like it or not. If your urine isn't pale by evening, you underdrank.

What Winter Training Actually Looks Like

Forget suffering through it. Forget "just getting through to spring". Here's what working with physiology instead of against it means. You ride less than summer, but harder when you do. You dress warmer than feels necessary. You stop before you shiver, not after. You get warm and eat fast. You drink whether you're thirsty or not.

Your power numbers look lower because physics doesn't care about your feelings. That's fine. You're not racing in January. But when March arrives and everyone else is rebuilding base fitness, you've still got your top end. You can go straight into proper training, not spend six weeks remembering how to ride a bike hard.

The research shows block periodisation produces superior adaptations with the same training time. Proper thermal protection prevents a 31% power loss. Cold exposure provides an additional training stimulus for mitochondrial development. The principles work. Apply them consistently and you'll arrive at spring with your fitness intact, possibly improved.

For ultra-distance riders, this approach means you can add volume productively in spring. You haven't spent winter grinding yourself down with long, slow, cold miles. You've maintained your intensity, your steady-state power, and your ability to respond to training stress. When conditions improve and you start building towards your summer event, you're adding volume to a solid foundation, not trying to rebuild everything from scratch.

The Mistakes Everyone Makes

Chasing summer volume in winter conditions. You can't. The conditions don't allow it and your body doesn't need it. Switch to blocks. For ultra-distance riders especially, winter volume is counterproductive. Save it for spring when you can actually complete quality long rides.

Underdressing legs because your core feels warm. Your torso generates heat. Your legs don't. Thermal bibs aren't a luxury item.

Continuing when you're shivering. This is ego, not training. You're depleting glycogen, not building fitness.

Slow cool-down after hard winter efforts. Get warm within 30 minutes. Your immune system notices the difference.

Drinking only when thirsty. Cold suppresses thirst. Drink by the clock instead.

Final Thoughts

Winter training isn't complicated. It's just different. Keep your muscles at operating temperature. Concentrate your intensity into focused blocks. Stop before you shiver. Recover aggressively. Drink by schedule.

Do that and you'll arrive at spring with your fitness intact, possibly improved. The riders who ground out endless slow winter miles will be starting from scratch. Whether you're targeting a local sportive, gran fondo or an Audax, the principle is the same. Winter is about maintaining quality, not chasing quantity. The volume comes later. The choice is obvious really.

References

Nieman DC. Exercise, infection, and immunity. International Journal of Sports Medicine 1994; 15(S3):S131-S141.

Ouellet V, Labbé SM, Blondin DP, et al. Brown adipose tissue oxidative metabolism contributes to energy expenditure during acute cold exposure in humans. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2012; 122(2):545-552.

Rønnestad BR, Hansen J, Ellefsen S. Block periodisation of high-intensity aerobic intervals provides superior training effects in trained cyclists. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2014; 24(1):34-42.

Slivka DR, Tucker TJ, Dumke C, Cuddy JS, Ruby B. Human mRNA response to exercise and temperature. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2012; 33(2):94-100.

Wallace PJ, McKinlay BJ, Coletta NA, et al. Effects of core and shell cooling on cycling time to exhaustion in the cold. Journal of Applied Physiology 2024; 136(1):66-77.